Visualising THE Climate Crisis

Cambodia, Laos, Thailand & Vietnam

A visual storytelling mentoring programme by the NOOR Foundation featuring works by:

Duy Đào, Jittrapon Kaicome, Nguyễn Thanh Huế, Ponita Keo, Saobora Narin, Satita Taratis, Savroun Ry, Sirachai Arunrugstichai, Southida Manixay, Trần Thái-Khương, Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, Wan Chantavilasvong

Supported by the Kingdom of The Netherlands and the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) in collaboration with Matca in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Generously supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of The Netherlands in Thailand, the exhibition showcasing the work produced during the programme will be part of the Angkor Photo Festival in Siem Reap, Cambodia between 19 of January to 02 of February 2024.

The exhibition will be presented on January 27 at 11:00AM with a guided tour accompanied by the photographers and at the presence of Mr. Jeroen Boonzaaijer, the Second Secretary of the Embassy of The Netherlands in Thailand.

The climate crisis is the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced. A delicate balance has been tipped over, unleashing a series of chain consequences the scale of which we are yet to grasp. As we witness the intensification of the crisis, we must come to terms with the fact that the complexity of the matter underscores a very simple fact: change is the only way forward. Acceptance, adaptation, and mitigation are our only chances to thrive in an uncertain future.

For eons, humans have relied on storytelling as a way to share knowledge, overcome the unknown, and pass on wisdom from one generation to the next. Being a carrier of collective memory, storytelling holds the very key to the future. We believe that images hold immense power, capable of creating an impact like no other communication tool. Visual storytellers hold the potential to make a critical difference in our understanding of the climate crisis, functioning as a bridge between complex science, political strategies, economic interests, and citizens.

For these reasons, the NOOR Foundation supported by The Kingdom of The Netherlands and ASEF created a dedicated space wherein authors from Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam could come together to work, share, and learn from one another.

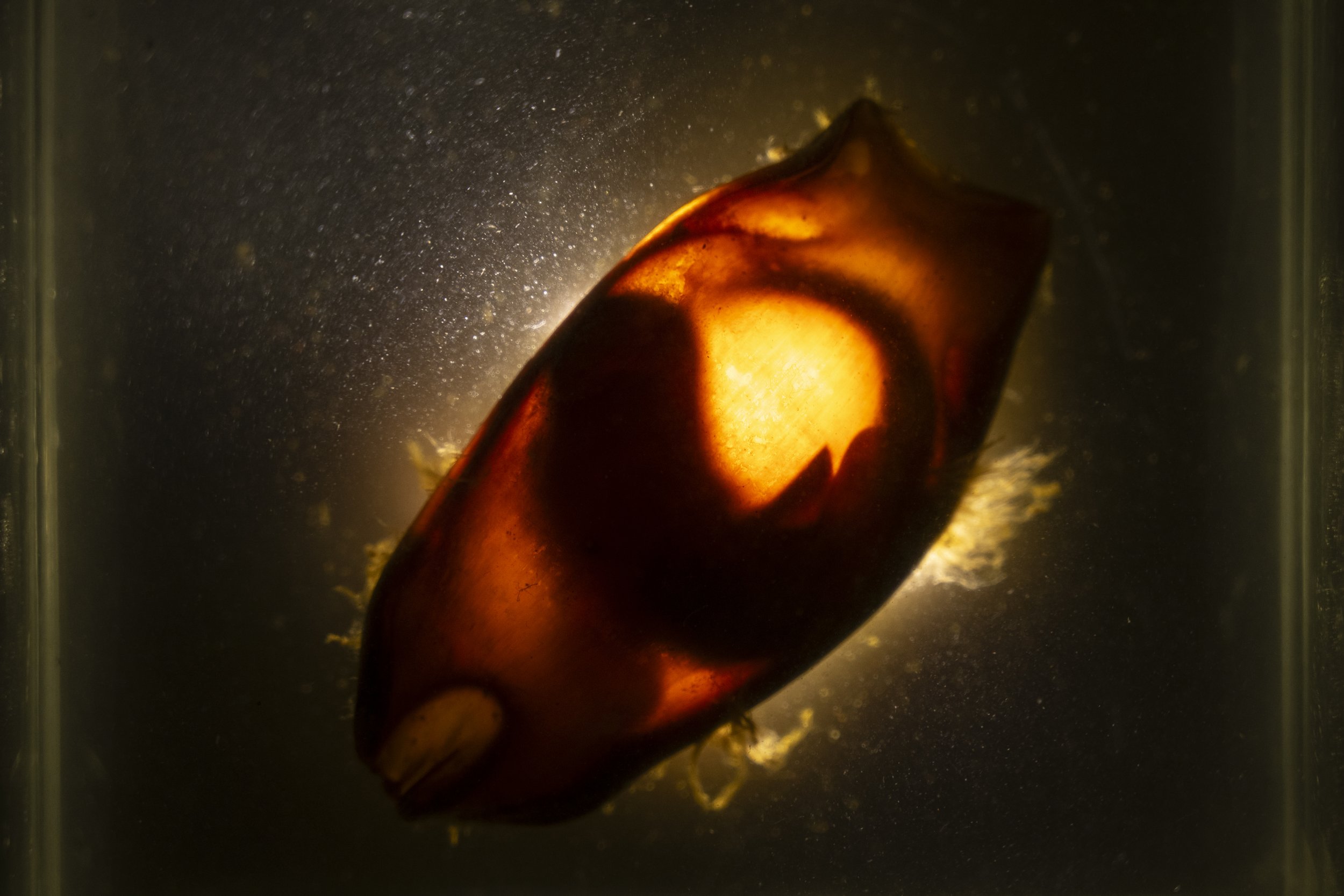

A giant freshwater prawn is pictured in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, on 28 August 2023. ©Thanh Hue Nguyen

Thailand, Chiang Mai. 22 January 2019. A farmer collects and gathers corn in the mountains. The collected grains are sold to the food industry. Due to the increasing demand in the global meat market, corn is widely cultivated. ©Jittrapon Kaicome

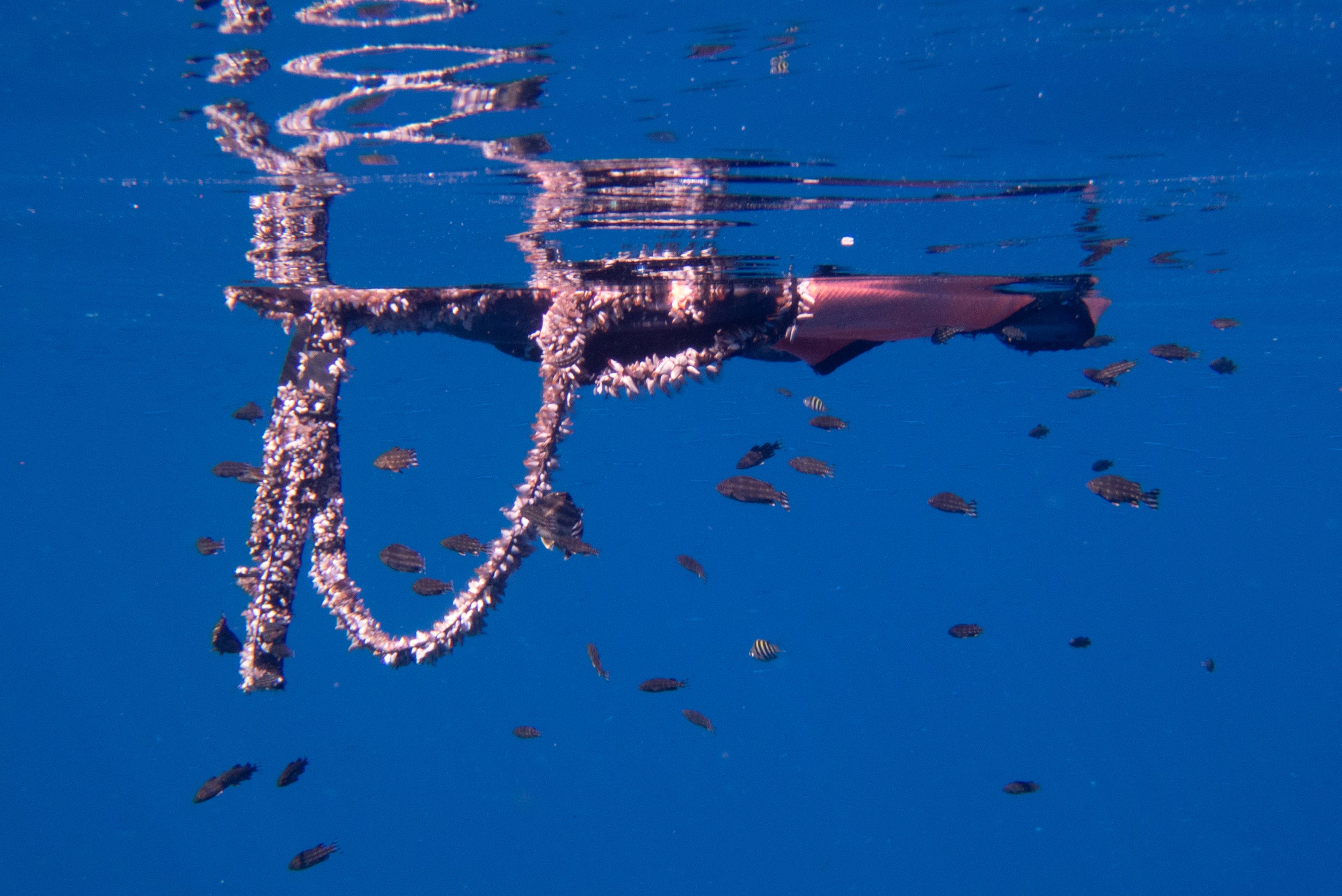

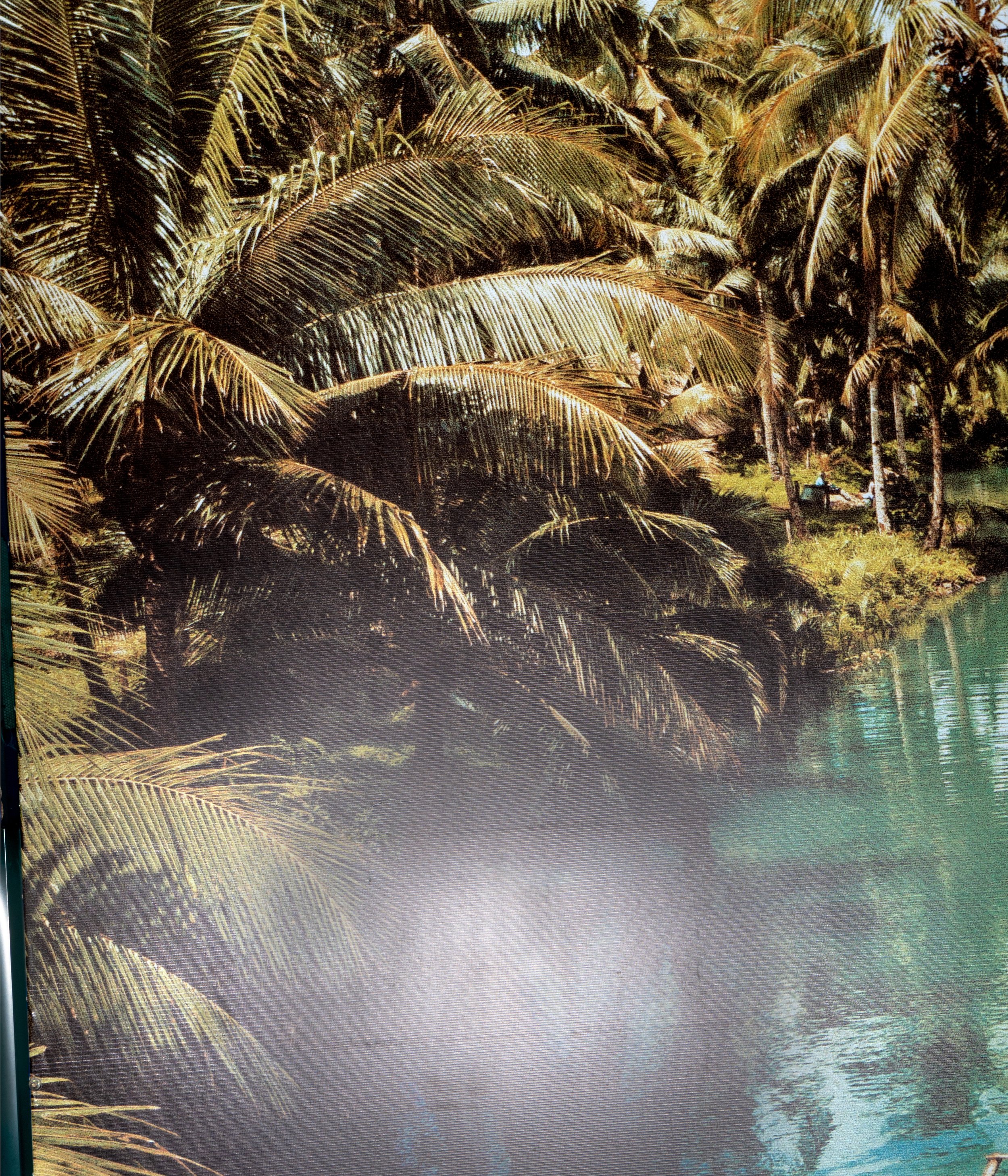

Fishermen in Trapeang Sangkae Community in Cambodia's Kampot province, prepare to boat out to fish in the mangrove forest nearby their village.© Roun Ry

Prachuap Khiri Khan, Thailand. Floating food packages are another prevalent ocean plastic debris that end up stranded on the beach. With its continuous exposure to heat and light from the sun, its GHG emission also continues. ©Wan Chantavilasvong

Guided by award-winning visual storytellers Kadir van Lohuizen (The Netherlands) and Linh Pham (Vietnam), the twelve authors worked on stories close to home in mainland South East Asia. The reality here paints a very strong picture: the climate crisis is here, right at our front door, and with it entire ecosystems mutate, migrate, and go extinct, and the chain of life they support changes irrevocably, often driven to the brink of collapse.

With their stories, the authors take us on a journey of discovery: from the impact of ocean acidification on the life oceans support to the human adaptation to evermore extreme heat waves. We are taken along the costs of Cambodia where, although deforestation of mangrove forests continues, grass root operations of reforestation fight it back while on the Mekong Delta, one of the regions most impacted by the climate crisis, we learn of a new surprising symbiosis between shrimps and rice plants which represents hope for local farmers.

One thing transpires from all the work with a crystal clear definition: If we are to stand a chance we are to recognize that the magnitude of this unprecedented crisis requires us to come together and act now. We hereby share with you twelve stories, twelve seeds of change, and invite you to water these seeds, to share, care, and grow together into something larger and more powerful than the sum of us.

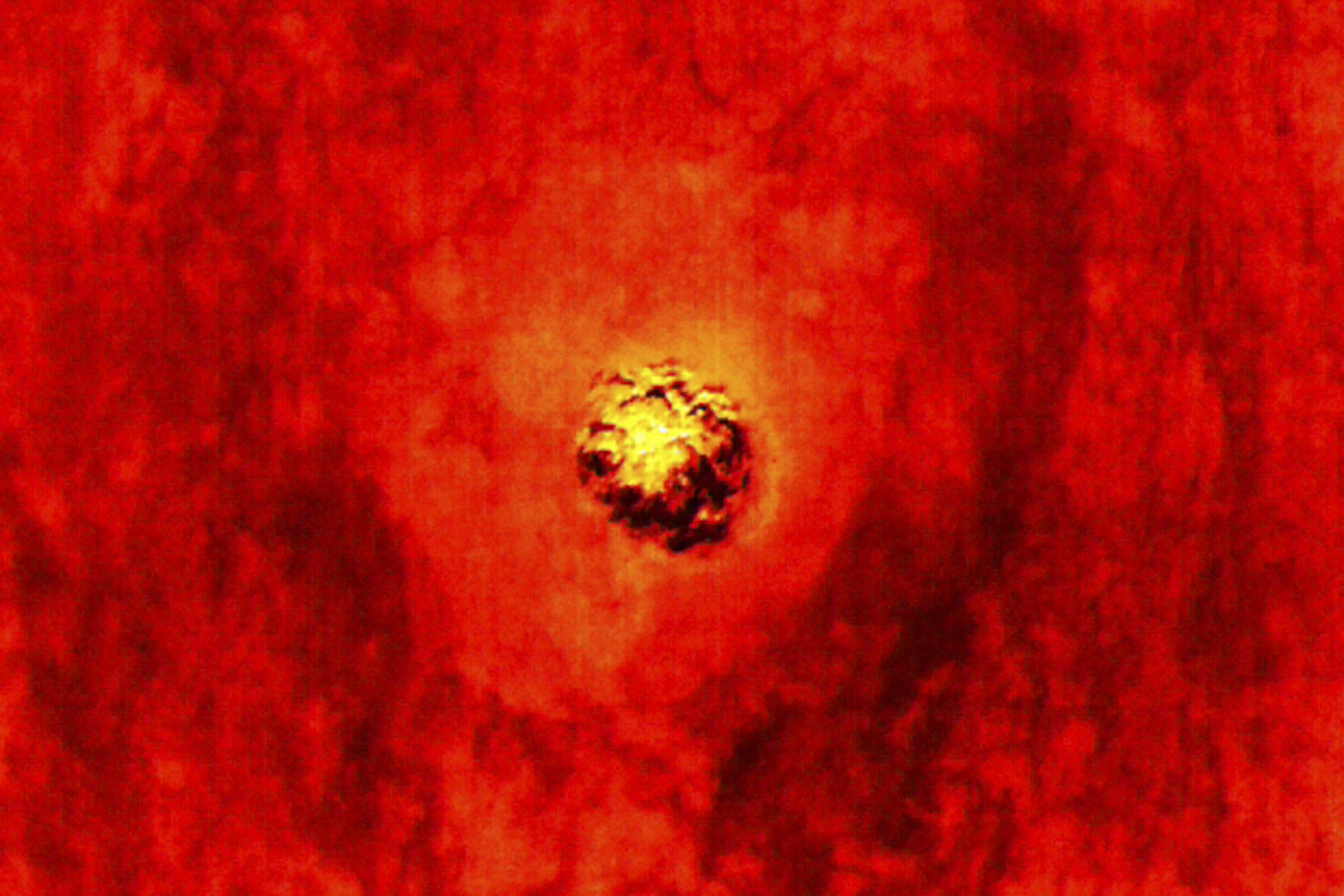

OCEAN PLASTICOSIS

The quiet force exacerbating the climate crisis

By Wan Chantavilasvong, Thailand

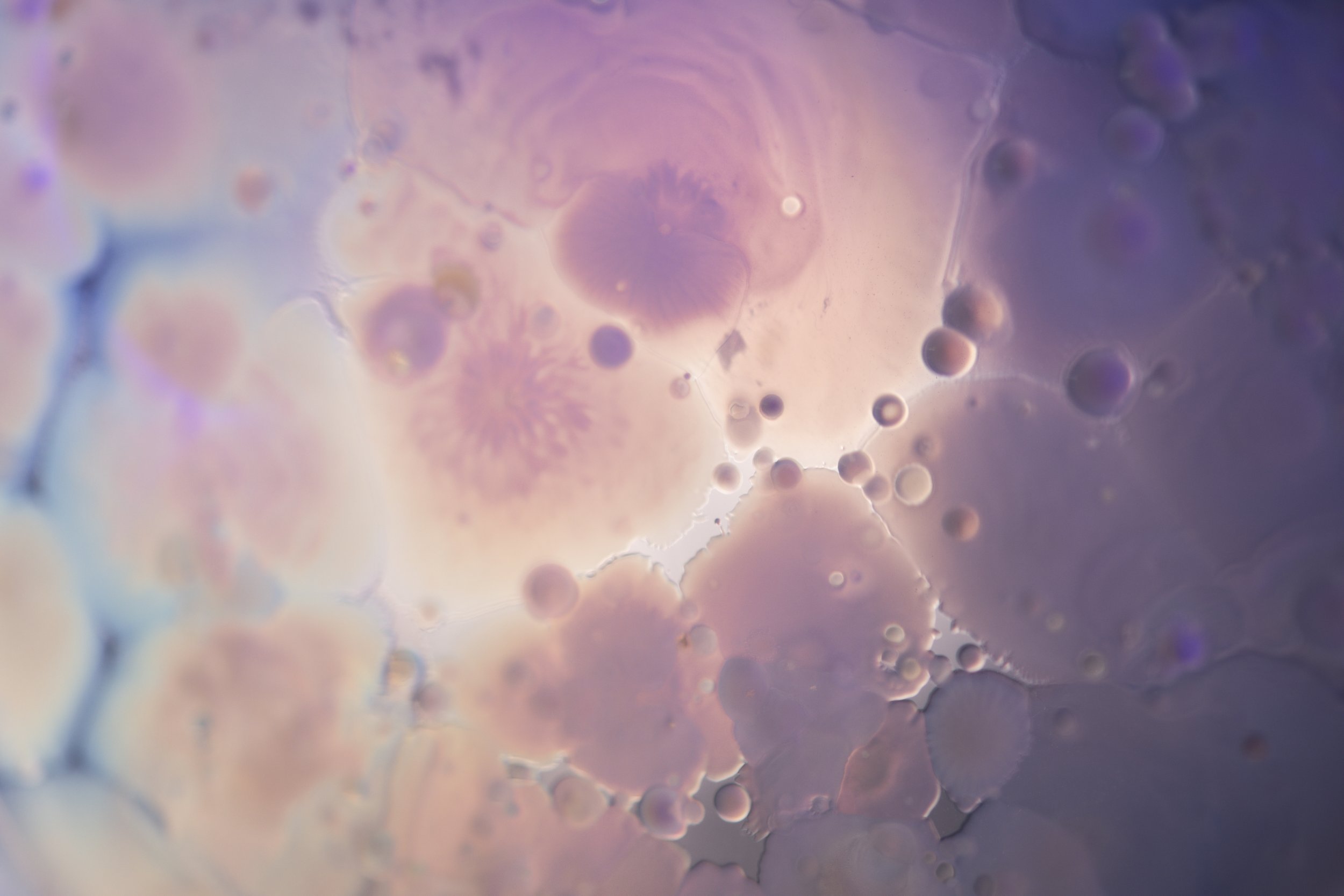

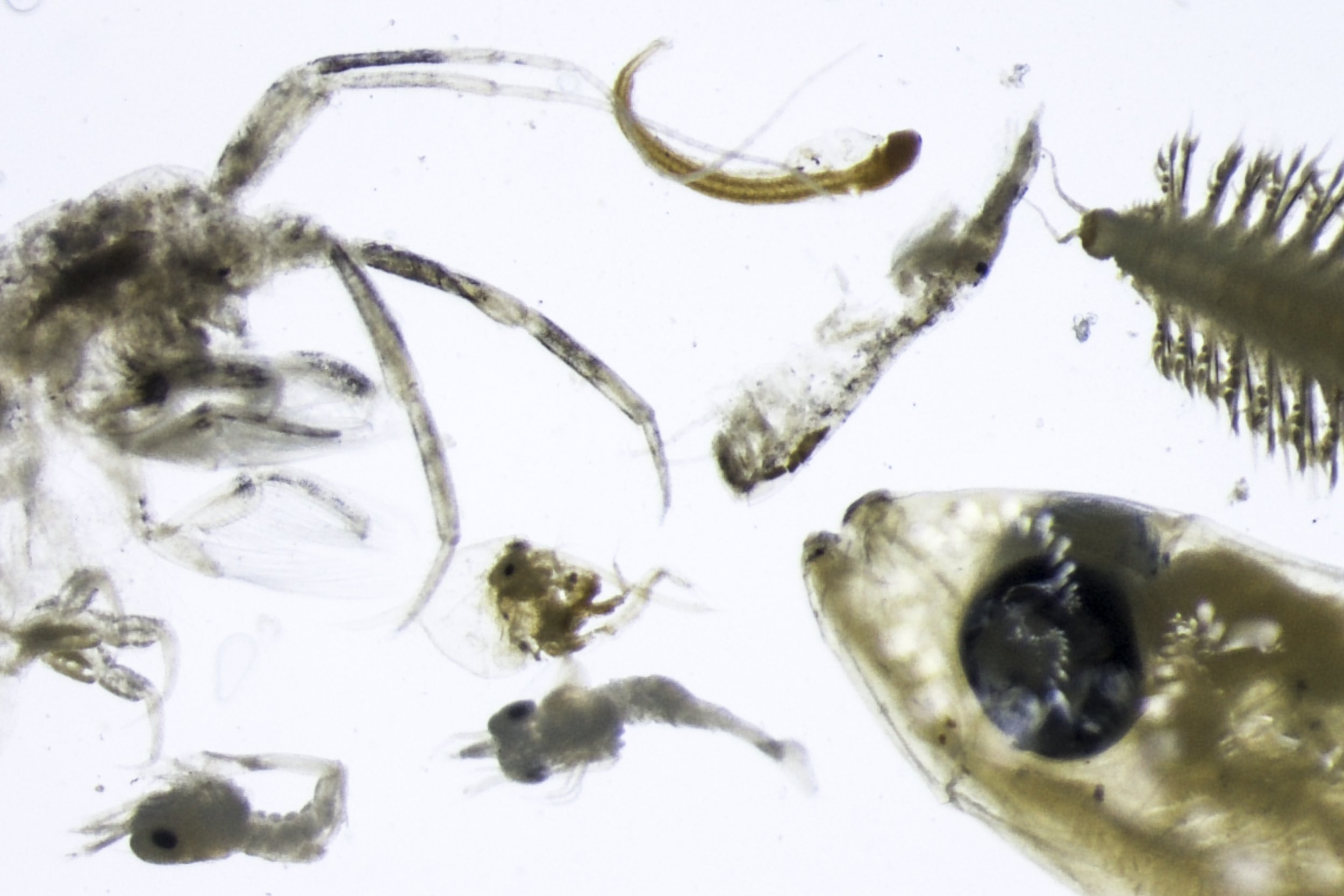

Plastic debris is a prevalent problem across the globe from the terrestrial to the oceanic environment. Many of us have heard about how plastic is causing plasticosis impacts on animals of all sizes—from big whales to fish, bivalves, as well as tiny zooplankton. However, as the ocean contributes greatly to the carbon sink processes, the frontier of marine science is beginning to learn more about how the plastic cycle may also impact the carbon cycle. In other words, we are at the cusp of understanding how plastics interfere with natural mechanisms of carbon capture, transferal, and sequestration.

What we already know is that greenhouse gas (GHG) is emitted at every stage of the plastic cycle from its production processes to its breakdown and decomposition processes. New studies also find that major photosynthesizing organisms of the world (phytoplankton) are also affected by plastic leachate exposure. Although phytoplankton still largely outnumber microplastic, a significant climate crisis contribution is not unimaginable if plastic usage and waste mismanagement trends continue.

Scientists estimate that roughly 50% of the oxygen production on Earth comes from the ocean—the phytoplankton. Through photosynthesis, phytoplankton is the main contributor to capture carbon from the atmosphere. As plastics can impact marine prokaryotes, the overall ocean’s contribution to carbon capturing may also be disrupted.

Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus are photosynthesizing bacteria in the ocean that contributes to about 20% of global photosynthesis, which is a fundamental part of the carbon cycle. Marine scientists globally are figuring out the relationship between the plastic cycle and the carbon cycle.

Marine Ecology Laboratory at Chulalongkorn University, Department of Marine Science Bangkok, Thailand. Microplastic strands founded in seashells near river fronts are put together with a diatom phytoplankton culture to exemplify the toxic dynamics of plastic leachate exposure.

Of the 9,200 million tons of global cumulative production of plastic between 1950-2017, around 58% of which have been discarded into landfills, dumps, or uncontrolled waste. The rest of the produced plastics are either still in use in the original form, in the recycled form, or have been incinerated. These numbers are expected to triple by 2040 without meaningful interventions.

Asia is contributing to 81% of global plastic emission to the ocean, and Thailand alone is contributing 2.33% (22,806 tons) in 2019. While Thailand’s plastic waste generation is about 3.5 million tons, 10 times less than that of the US, the mismanaged plastic waste being emitted to the ocean is 10 times higher in Thailand than the US.

These amounts are also rising annually.

Wan Chantavilasvong is an independent urban researcher, a photography artist, and a conservation diver based in Bangkok, Thailand. She began her photographic journey through her travels to different continents. Nowadays, as she became more curious about the environmental impacts and urban society, she has started to explore ways photography can be used to capture her unique thoughts, to open new gateways for more questions, and to remain curious about the world.

Wan Chantavilasvong

https://wanc.space

Instagram: @wan.chtvlv

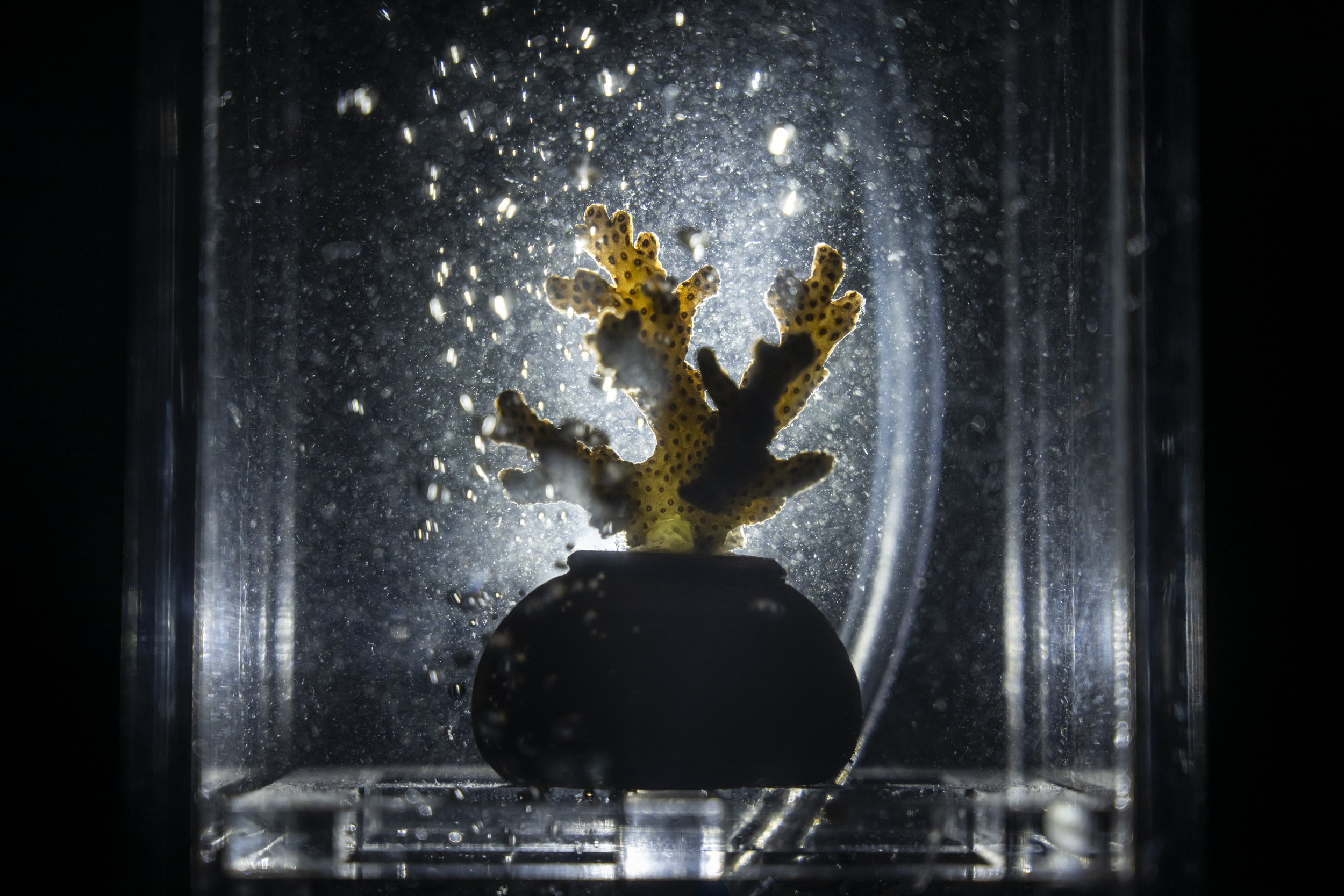

pH 7.8: The future of the acidic sea

By Sirachai Arunrugstichai, Thailand

Covering over 70% of the Earth's surface, the oceans have a critical role in regulating the climate and are the largest carbon sink of this planet, where they absorb approximately 30% of carbon emissions from the atmosphere. However, the absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide has gradually changed the chemistry of seawater, making it increasingly acidic in a process called “Ocean Acidification”. Since the industrial revolution, the ocean pH has dropped from 8.2 to 8.1, but this 0.1 unit already represents a 30% increase in the acidity of the oceans, which is the fastest rate at least in the past 300 million years of earth's history.

Various studies have investigated the effects of ocean acidification on the marine environment in the past two decades. Most scientific studies indicate that increasing acidity has detrimental effects on various aquatic organisms to different degrees. Calcifying organisms such as shellfish and corals are especially susceptible to this condition since the acidic water has fewer carbonate ions available for them to build shells or skeletons, which results in the dissolution or malformation of the calcified body structures. Although some taxa may be able to withstand a fluctuation in acidity more than others, such as fish, they are still susceptible to negative impacts from the acidic condition during early life stages, where the physiology, development, and behavior are shown to be affected in experimental studies, resulting in a higher mortality rate, and affecting recruitment and recovery. Since different fauna and flora react to elevated acidity differently, another potential effect of acidification is the restructuring of the marine community, as has been shown in plankton and even microbe communities. The varying degrees of impacts throughout the community could potentially affect the whole food web, cascading through the trophic level in the marine ecosystems, and may eventually change the oceans as we know them today.

Sirachai Arunrugstichai

https://www.shinsphoto.com/

Instagram: @shinalodon

Sirachai (Shin) Arunrugstichai is a Thai photojournalist and a marine biologist from Bangkok, Thailand, with a specialization in marine conservation stories. Shin originally picked up photography to document marine biodiversity while working as a field biologist. However, after realizing the power of photography for communicating serious conservation issues with the public, he later shifted his career toward photojournalism. Shin is a National Geographic Explorer and an Associate Fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers. He regularly works for conservation organizations, such as IUCN, WildAid, Ocean Conservancy, Greenpeace, Save Our Seas Foundation, and more, while also providing news coverage for Getty Images as a stringer. His photographs have been published in National Geographic, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Guardian, among others.

Although his focus is on photojournalism, Shin still often collaborates on scientific studies of sharks and rays and research expeditions in the waters of Southeast Asia, which he calls home.

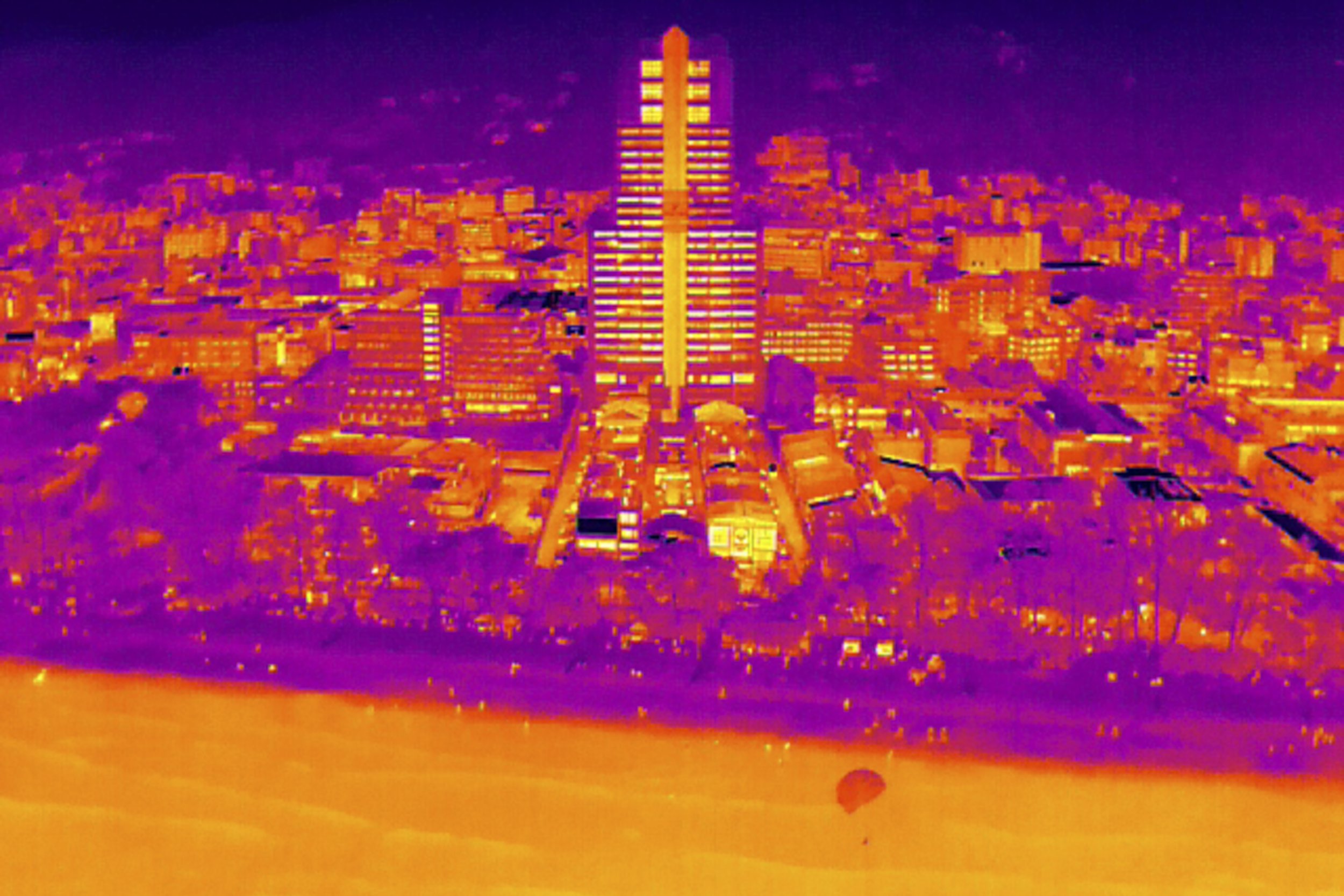

PArallel world

by Satita Taratis, Thailand

“Parallel World, the ‘other’ end where minutes pass by, never-ending, as if there is no way for intersection with ‘our’ world. We may have glanced around, but we never really see it there. We listen to its sounds, but they are never truly heard. Another world exists in parallel, yet we feel like we have nothing to do with it.”

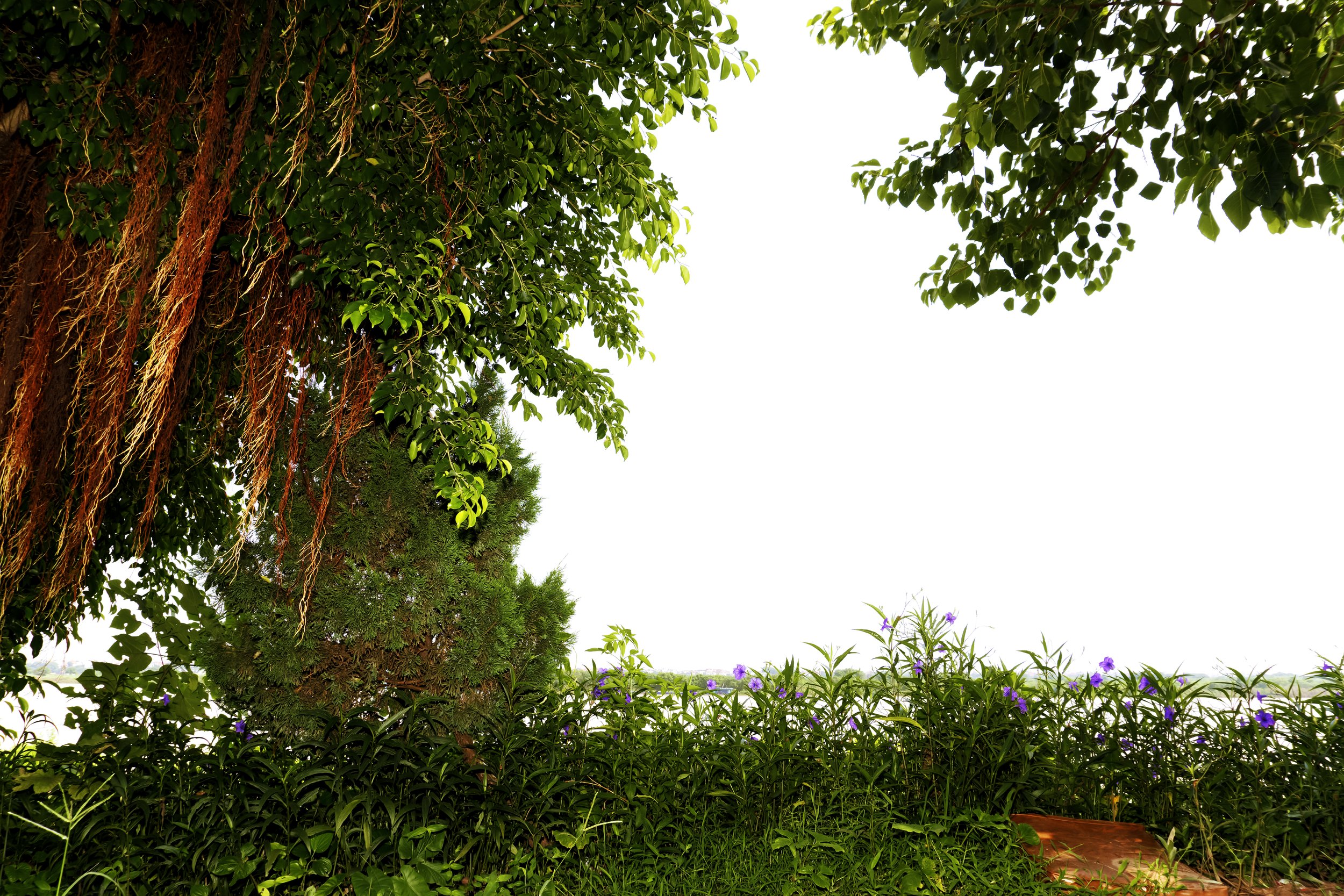

Khun Samut Chin Village, Samut Prakan province, only some forty kilometers away from Bangkok is a village fighting for its life, being the most affected by coastal erosion in Thailand. As Google Earth Time-lapse shows, between 1984 and 2023, a kilometer of coastal land is already gone, not to mention a reduction from 400 households to only 178 today.

Some families were forced to move 11 times in their lifespan. For them, the fight against the climate crisis is long and winding, it has been a part of life.

We hear villagers talk about remnants of an abundant past in the land they lived on, where with bare hands you could catch prawn and crab, just like that. Today, the plentiful land is no more; all swallowed up by the greed of humans, a destruction so vast from man-made dams upstream. Human civilization has created irreversible effects on the Chao Phraya River estuary in wide-ranging dimensions.

Data from Climate Central (2019) showed that sea levels will rise to 2.1 meters within the year 2100. The flood will affect 300 million people along the coastlands of Thailand, China, Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam. By then, Baan Khun Samut Chin would be wiped off the map of Thailand.

“Climate crisis — if we can’t see it, nor feel it right by our doorsteps, would we be able to feel the drastic effects on our lives?”

Satita Taratis was born in 1993 in Bangkok, Thailand, and graduated in applied computer science – multimedia. During her university days, she liked to spend her free time trekking and learning the way of life of Karen people, an ethnic minority group in Thailand. These experiences changed her life and how she sees the world. Nature gives her inspiration and energy, and that is where she found her passion in visual storytelling, which helps her to deepen her understanding about this world. Currently, Satita is a freelance photographer with focus on human relationship with nature.

SATITA TARATIS

http://mymory.space/

Instagram: @mymory.space

The last mangrove

Loss and restoration of mangroves in Cambodia

By Roun Ry, Cambodia

Cambodia, a country with 443 km of coastline, lost almost half of its mangrove forest between 1989 and 2017 mainly due to salt farming, charcoal production, and shrimp farming. Mangrove forests are essential to the coastal ecosystem as they help prevent coastal erosion, protect the water quality, and reduce coastal flooding. Moreover, they also provide a habitat for various terrestrial and marine species including economically and ecologically important fish that support communities living along the coastlines.

About 75 to 80 percent of people living on the Cambodian coast rely on fishing so without mangrove forests their lives will become increasingly difficult.

As temperatures rise due to the climate crisis, the polar ice caps melt which causes the sea level to rise. If humans don't work together to preserve and grow back Mangrove forests to prevent coastal erosion, we will all be left to face the catastrophic effects alone.

As communities realize that the destruction of mangroves severely affects their lives, they have begun to work together to try to save the remaining mangroves and restore what was lost. My project hopes to tell this story of the severed relationship between the coastal people and their land, and the attempts of restoration and reconciliation in an increasingly hostile climate.

Roun ry

https://www.rounry.com/

Instagram: @rounry

Roun Ry is a freelance photographer based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. His photography primarily focuses on social and environmental issues in Cambodia. His most recent project delves into the lives of people in Tonle Sap Lake and the impact of dam construction in Stung Treng on the indigenous communities in that region. In 2016, Roun had the opportunity to attend a masterclass led by renowned photographers Antoine d’Agata and Sohrab Hura during the Angkor Photo Festival. He has since been featured in publications such as Al Jazeera, China Dialogue, Asia Society, VOD News, and New Naratif.

beauty and the pigs

By Ponita Keo, Cambodia

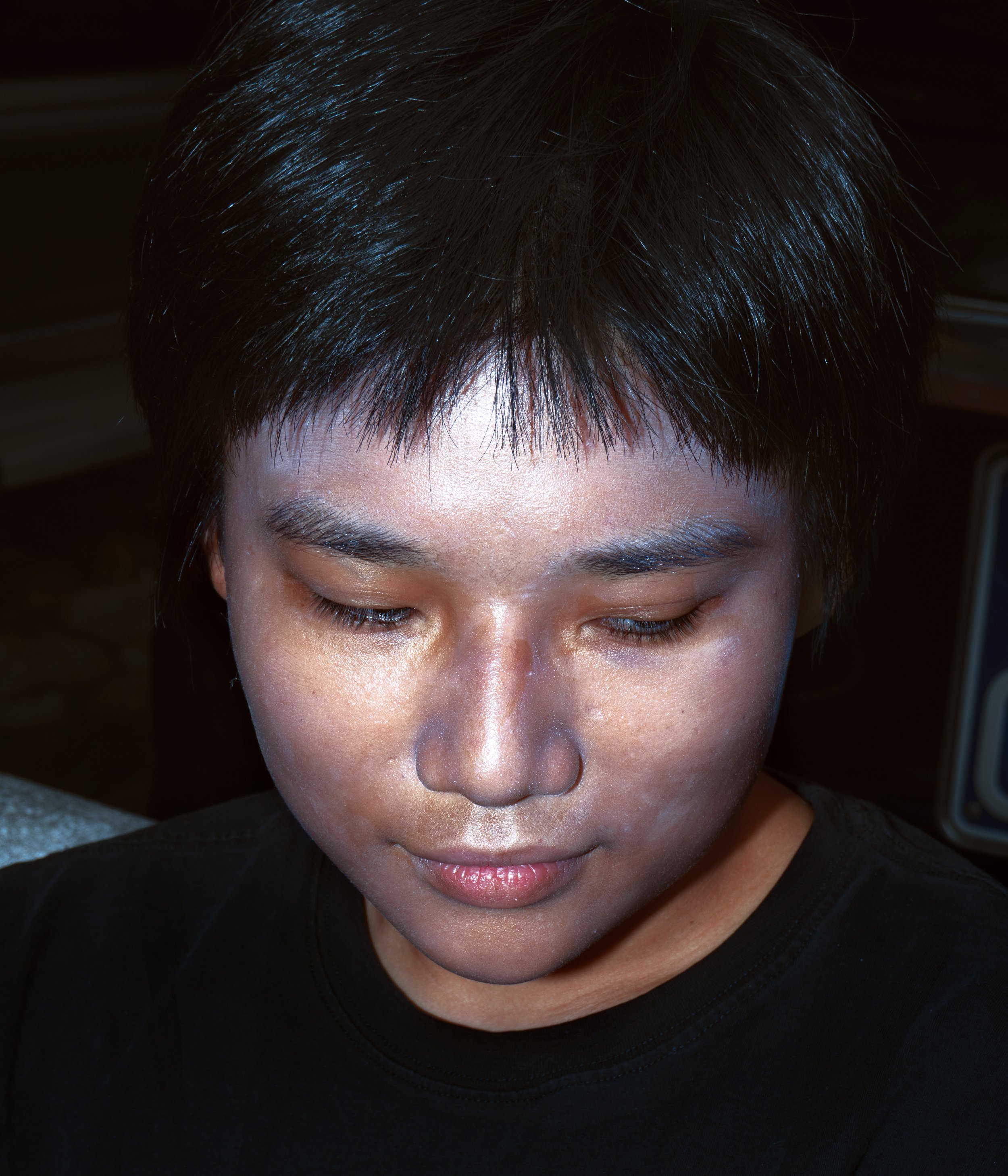

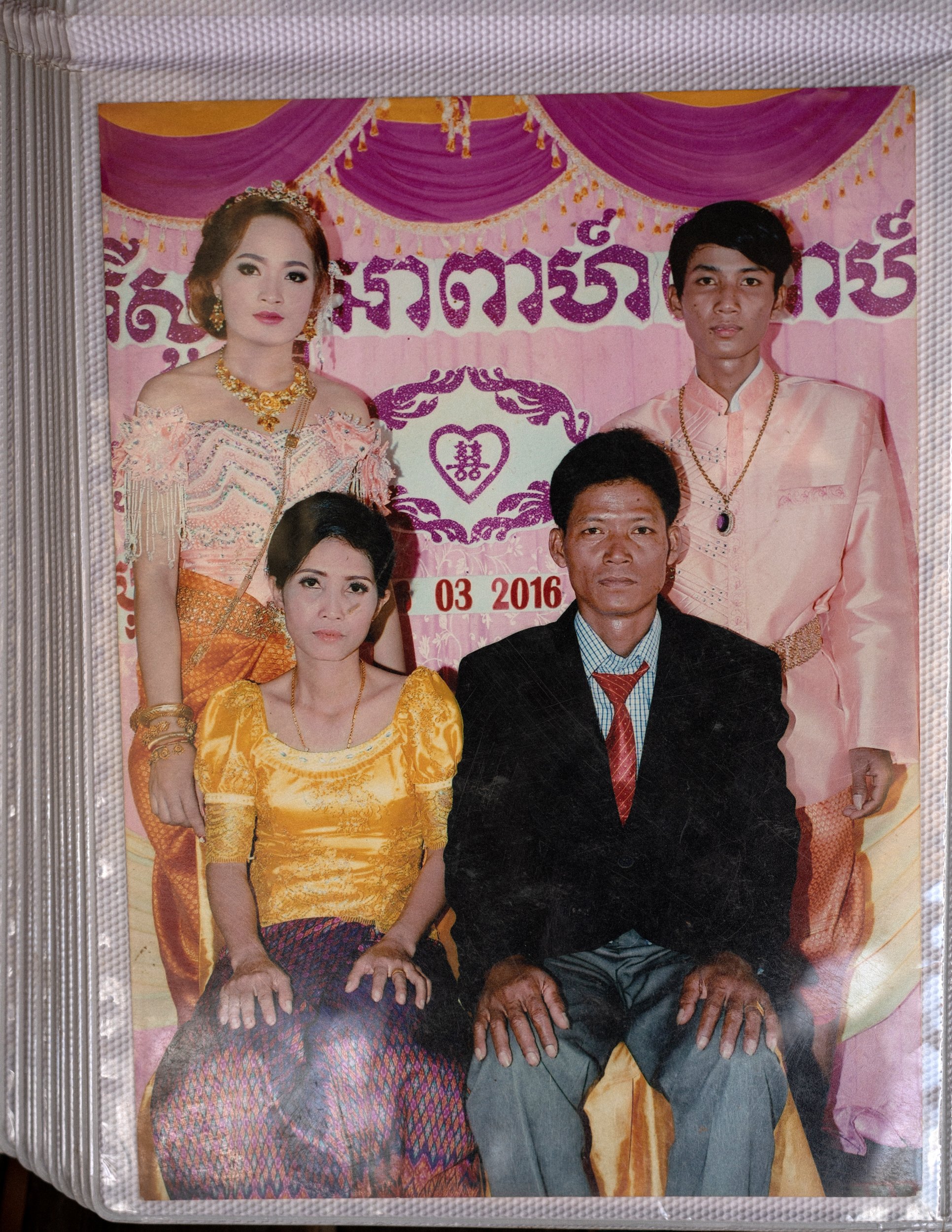

Beauty and the Pigs delves into the world of Samin and her sisters, Sameat and Sreymom. Potentially the last inheritors of their family’s cherished rice farming tradition, the Kan sisters and their families live in Battambang, a major rice growing province, where for generations their family has cultivated the land, harvesting not just rice but a sense of identity.

Today, the sisters stand at a crossroads as changing climate patterns, including floods, droughts, and unpredictable rainfall, have disrupted their once familiar rhythm of sowing and reaping, posing a threat to their livelihood. Added pressures of mounting debt and anxieties about an unknown future have pushed these women to seek supplementary forms of income. To try and make ends meet, they now raise pigs as livestock and run a makeshift beauty parlour part time.

The narrative mirrors the struggles echoing throughout Cambodia's rice growing regions. While rice farming remains central to the nation's economy and identity, data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has shown that recent unpredictable weather patterns have directly impacted traditional rice production, placing significant challenges on farmers and rural communities.

The experience of the three sisters resonates far beyond the provincial borders, reflecting the roles of women in Cambodia's patriarchal society. Research from UN Women highlights that women often shoulder the majority of agricultural responsibilities, including planting, weeding, and harvesting. These traditional roles as caregivers, farmers, and family pillars thus expose them to disproportionate risks from severe environmental shifts.

The series is a depiction of the sisters' lived realities and their quiet triumphs in the face of environmental obstacles. In producing this body of work, I sought to understand what it means to be a woman in these challenging circumstances.

Beauty and the Pigs is no extraordinary tale but a common one that reflects the hopes and worries of countless grandmothers, mothers, sisters, and daughters across Cambodia, and beyond. It serves as a reminder that what might seem ordinary to some is, in fact, extraordinary in its familiarity.

““We can no longer rely on the sky - only each other and ourselves”

”

Ponita Keo (b. 1991) is a Cambodian documentary photographer and visual artist whose work often explores notions of womanhood and the nuances of the female experience. Her approach to storytelling is rooted in reflexivity and anthropology, with a penchant for allegory and subtleties in her visual narratives. Ponita was formerly a news editor, before shifting to pursue creative visual storytelling in 2021, where she trained with Magnum Photos and obtained a masters in photojournalism the following year. Aside from her artistic and documentary work, she is also a freelance photographer, videographer and art director, dividing her time between Cambodia and France.

ponita keo

https://ponitakeo.com/

Instagram: @ponitakeo

come and see

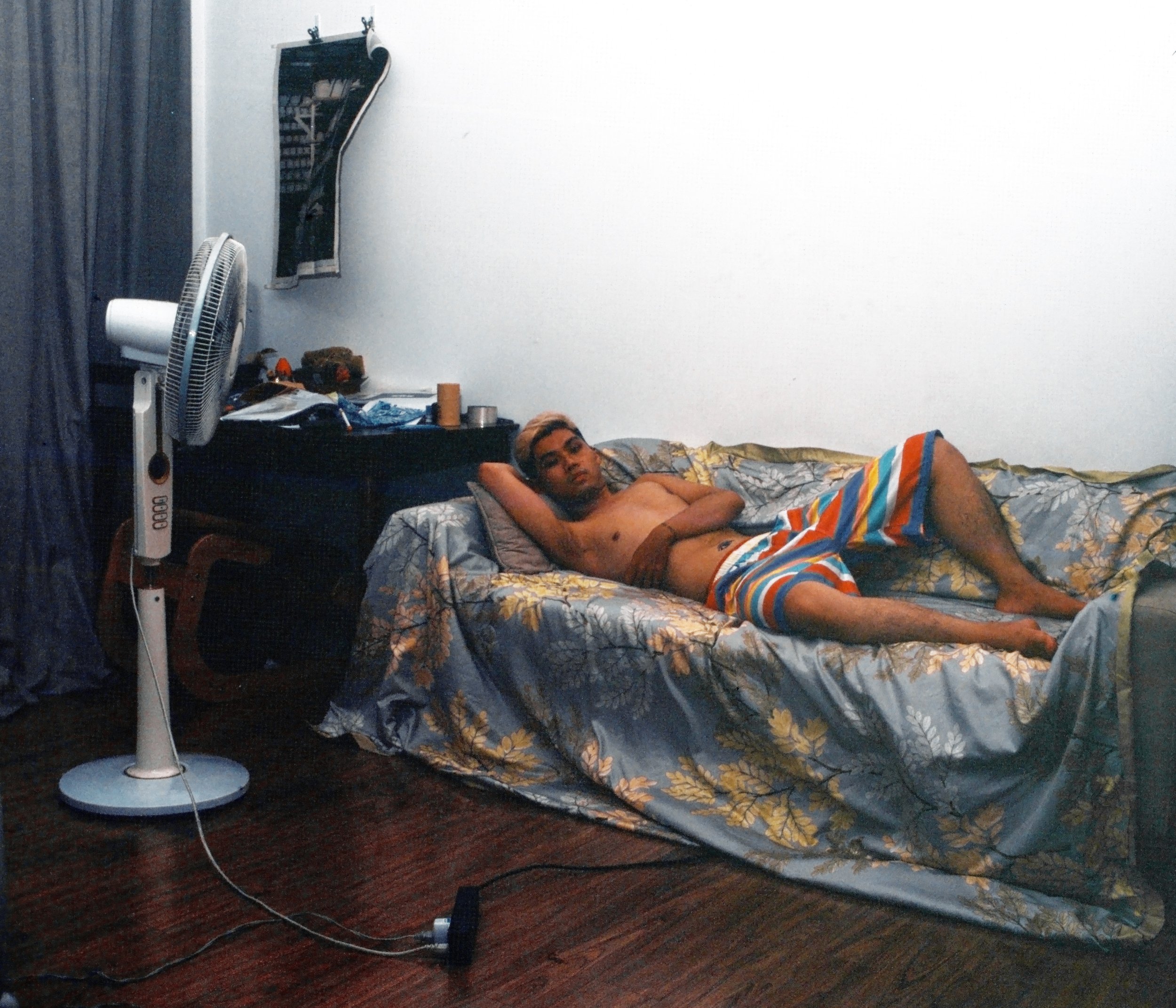

Adaptation to heat waves

By Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, Vietnam

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) “heatwaves, or heat and hot weather that can last for several days, can have a significant impact on society, including a rise in heat-related deaths.

Heatwaves are among the most dangerous of natural hazards, but rarely receive adequate attention because their death tolls and destruction are not always immediately obvious.”

Once an alarm for every summer, the fatigue “hoa mắt” is now recognized as the norm for its increasing heat: no week is the hottest week recorded if every week is.

How can the average person be a victim of his existence? What are the signs? What are the cues? What is the evidence of our doing that is so horrific? Why do we do what we do?

The same floral motifs of the duvets used to cover up stores, houses, produce, and floras to keep from sun damage demonstrate the increasingly common phenomenon that happens when a person is under the scorching sun without protection.

Adaptation to heat-induced fatigue includes protection of oneself though its consequences are apparent: consumption of single-use plastics, overbuying, over-mining, etc.

All of this led to the acceleration of the crisis as we know it today.

Vân-Nhi Nguyễn

https://vannhinguyen.com/

Instagram: @vnnhi

Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, a Hanoi-based photographer and artist, discusses cultural identities and social concerns via aesthetic research and theatrical staging, proposing interpretations and challenging assumptions. Vân-Nhi has exhibited at and received awards from various institutions, namely V&A Museum Parasol Foundation, Aperture Portfolio Prize, and PhMuseum among others.

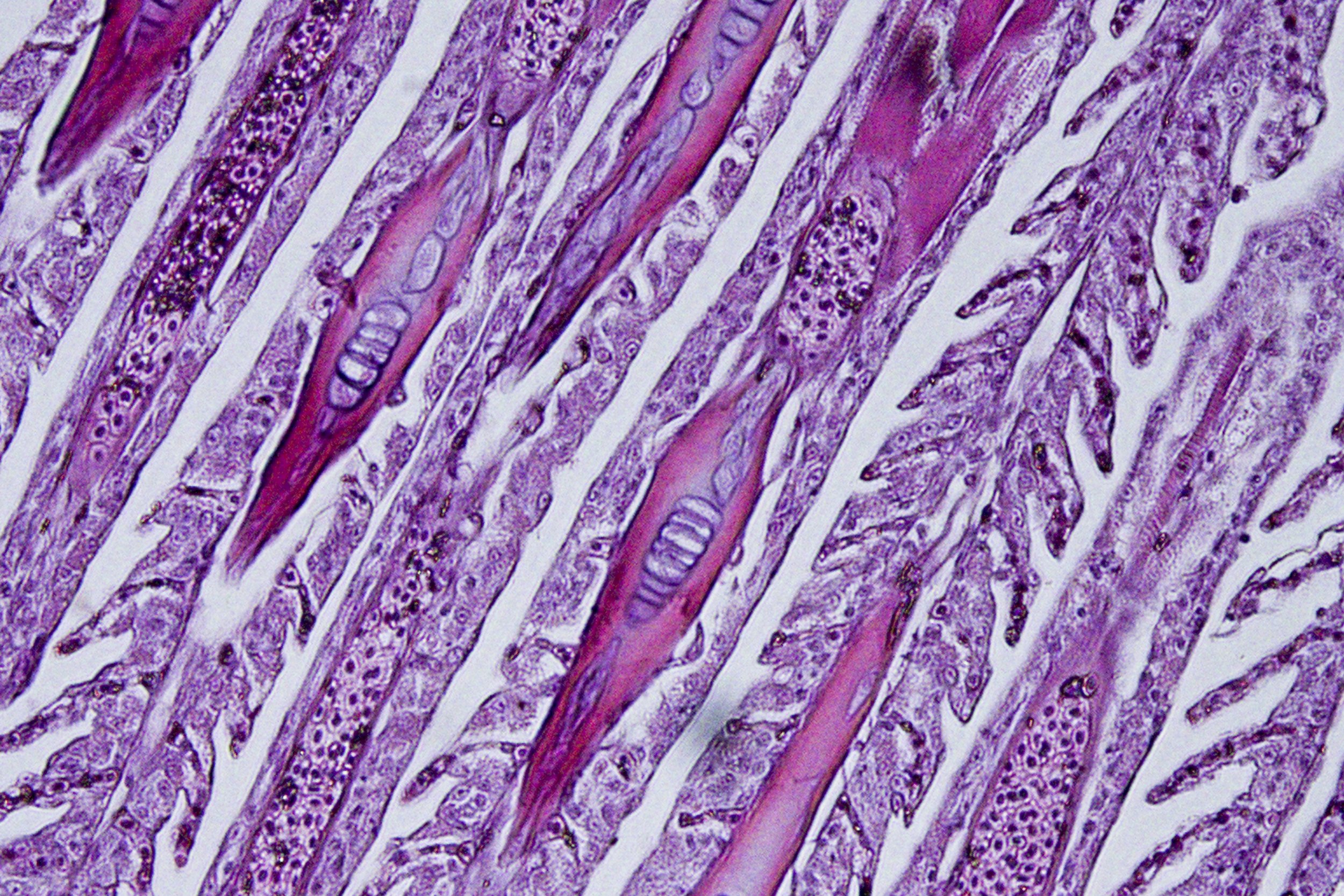

The shrimp hugs the rice plant

Dealing with the climate crisis in the Mekong Delta

By Nguyễn Thanh Huế , Vietnam

The Mekong Delta of Vietnam, the country's leading producer of rice and seafood, faces regular challenges from saltwater intrusion during the dry season. This intrusion occurs through the river mouths. During this period, it becomes impossible to cultivate rice in most coastal areas, and shrimp farming is also impacted by abnormal rainfall and prolonged rainy seasons. However, the rice-shrimp model, also known as "The shrimp hugs the rice plant," provides a viable solution.

"The shrimp hugs the rice plant" has proven to be efficient, sustainable, and environmentally friendly, resulting in three times higher yields than rice monoculture and nearly double the output of standalone shrimp farming. In this model, farmers allow saltwater to enter the rice fields to facilitate shrimp breeding during the dry season. They then use fresh water, primarily rainwater, to cultivate rice in the same area during the rainy season. Before introducing fresh water for rice cultivation, people stock the shrimp when the water's salinity level is ideal for its growth. Rice plants also play a role in purifying the water for shrimp farming, as shrimp feed on the plant-based food.

The adoption of the rice-shrimp model in the Mekong Delta provinces is expanding rapidly. For instance, in Bac Lieu province, the combined area for intercropping rice and cultivating shrimp has increased by 21.6 times, growing from 600 hectares in 2017 to 13,000 hectares in 2023.

Shrimp farmers load to classify with harvested shrimp in Bac Lieu province, Vietnam, on 17 June, 2023.

Farmers harvest rice in a paddy field in Bac Lieu province, Vietnam, on 23 August 2023.

Shrimp farmer Le Tan Lap feeds shrimps with coconut at his farm in Bac Lieu province, Vietnam, on 24 August 2023.

A worker works at a giant freshwater prawn product company in Ca Mau province, Vietnam on 25 August 2023.

A boy harvests shrimp at his family pool in Bac Lieu province, Vietnam, on 23 August 2023.

Nguyễn Thanh Huế

http://www.thanh-hue.com/

Instagram: @jadenguyenth

Thanh Hue is a Hanoi-born freelance photojournalist currently based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Her practice falls within the socially conscious documentary tradition, with a focus on human-centred issues, specifically portraits of people in their living spaces. Her works have been published in VnExpress, Reuters, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Mekong Eye, and U.S. News & World Report, among others.

She is a member of Diversify Photo and VII Academy alumni.

tears of dragons

The water well drillers

By Trần Thái-Khương, Vietnam

Ca Mau, a coastal province located in the southernmost region of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, is recognised as one of the most vulnerable areas in the country regarding the climate crisis.

According to one of the scenarios, if the sea level rose by 25 centimetres, approximately 85.4% (equivalent to 4,700 square kilometers) of the province's total natural area would be submerged, displacing about 200,000 households by 2040.

Ca Mau is the only place in the Mekong Delta without freshwater supplement from upstream Mekong River, leading to a high potential of saltwater intrusion.

According to the Center for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation in Ca Mau province, the province has 247 centralised water supply stations, but more than a third of them are not working due to lack of funds. Around 75% of Ca Mau's families rely on man-made water wells as their primary source of freshwater for daily needs and economic activities. However, Ca Mau is facing a decline in water resources due to the effects of the climate crisis and quality degradation due to human activities and production.

Each year, land subsidence in Ca Mau surpasses the rate of sea level rise significantly. Over-exploitation of groundwater is one of the factors causing it. The local government has introduced policies to restrict small-scale groundwater extraction. The longing for a stable and abundant freshwater source has persisted for generations in this region. This is the story of water well drilling - a profession that has endured for generations in the Mekong Delta despite current challenges and an uncertain future.

In the foreseeable future, the role of water well drillers in serving rural communities may cease to exist.

Trần Thái-Khương is a Vietnamese photographer based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. In 2008, after graduating from a multimedia design program, Khuong began exploring himself through photography.

He started working as a fashion and commercial photographer. He soon built up an extensive portfolio of photography projects published in many magazines. Aside from professional commissions, Khương conducted a handful of independent documentary projects. Since then, Khương has expanded his coverage to other subjects such as nature, culture, healthcare, animal welfare, and human life stories.

Trần Thái-Khương

Instagram: @trthkhuong

burning cornfields

From table demand to climate crisis

By Jittrapon Kaicome, Thailand

Corn is widely cultivated in Thailand and Southeast Asia as an important component of animal feed for the meat industry, which has grown rapidly in recent decades to meet global demand. However, the food system has become a burning issue that threatens our health and contributes significantly to the climate crisis.

Thailand is one of the largest animal feed producers in the region. The meat-producing conglomerates manage the entire food supply chain from corn harvest to meatpacking. Between 2014 and 2019, Thailand's poultry exports have nearly doubled. In addition, keeping pets has become a new worldwide trend after the recent COVID-19 outbreak. The latest data shows that Thailand is now the fourth-largest global exporter of pet food.

The corn cultivation practice requires the burning of the corn stubble. The agricultural burning compounds the haze issue from forest fires. Chiang Mai, my hometown in northern Thailand, has been choked by smog for a decade and the city was ranked the most polluted city in the world in March 2023. Every year, the Mekong region is blanketed with transboundary haze from February to April. Despite staying indoors, my mouth went dry from inhaling the fine particles.

Not only does this farming practice pose health risks to surrounding communities, but it also contributes significantly to the climate crisis as the burning releases large amounts of carbon dioxide. Not to mention the fact that corn cultivation has led to enormous deforestation of ecologically important forest areas. In the last twenty years, more than 800,000 acres of land in northern Thailand have been converted to monoculture.

Amid the growing concerns, meat substitutes from plant-based ingredients have begun to make their way into the market. The new food trend promises to become a sustainable solution to cut down the demand for corn. However, due to its high price, it remains accessible to only a few groups of people.

Building food security is on the global development agenda. The United Nations estimates that 68% more food will need to be produced by 2050 to feed enough of the future population. Meanwhile, the world today faces extreme heat and reaches the highest temperatures ever recorded. It is important to understand how our dining table has played an important role in the health concerns and climate crisis.

Jittrapon Kaicome is an independent photojournalist based in Chiang Mai, Thailand. His projects highlight current affairs, environmental crises, human rights, animal welfare, and the struggles of marginalised communities, including the ethnic armed conflicts and displaced persons along the Myanmar-Thailand border. In 2014, he began telling stories from his hometown during the annual air pollution crisis in northern Thailand. Having grown up in Chiang Mai, a city of many ethnicities, Jittrapon feels compelled to draw attention to the underrepresented ethnic communities in the region.

His works have been featured in Le Monde, Liberation, and many other publications worldwide.

jittrapon kaicome

https://www.jittraponkaicome.com/

Instagram: @jittrapon.kaicome

rust

By Duy Đào, Vietnam

I vividly remember the sensation of a parching wind sweeping across my cheeks and the relentless, sweltering heat of this region. An enigmatic man finds shelter within a modest abode, his gaze fixed upon the arid, scorched expanse of what was once a ripe rice field, now desiccated and devoid of bounty. Amid this destitution, children sit, emblematic of the meager soil's forsaken vitality. The land, bereft of human presence, is a realm where growth and development seem unattainable. During this journey, I found myself retracing the path to Phan Dung, situated 30 kilometers from the town center. A focal point for 238 Raglai households, it stands as one of the three ethnic groups residing in the northern precincts of Tuy Phong district, Binh Thuan province. In this enclave, livelihoods are predominantly shaped through the practice of agriculture and animal husbandry, with a few individuals making the descent into the town or venturing towards the mountainous terrain of Lam Dong in search of novel opportunities.

As per the records of the Department of Natural Resources and Environment in Binh Thuan province, Phan Dung undergoes two distinct seasons: a dry phase and a monsoon period. With an average humidity of 83%, the landscape experiences the harsh glare of the sun from April until mid-August, registering the zenith of 41.2 degrees Celsius in April 2022. However, the climate in this locale is becoming more unpredictable mainly due to the climate crisis. This has perpetuated a continuous spell of scorching sunshine and a drastic decline in rainfall, both of which have exerted a considerable toll on the community's production endeavors in Phan Dung.

The populace of Phan Dung is an offshoot of the Raglai tribe, who migrated from Ninh Thuan province to Binh Thuan. Here, they sustain themselves by cultivating rice and corn, following the rhythm of the two annual seasons. Nonetheless, the capricious climate shift, an offshoot of climate change, has led to relentless heatwaves and abrupt rainfall reduction, significantly impinging on the productive rhythms of Phan Dung's inhabitants. The cultivation of rice and corn, relegated to subsistence-level efforts, remains bereft of sophisticated techniques. With limited access to advanced agricultural methods, yields remain paltry. A complex spectrum of weather-related risks — ranging from droughts and water scarcity during the dry season to flooding, hillside erosion, and crop diseases in the rainy season — impose substantial limitations on sustained agricultural practices, preventing balanced development in comparison to other communes within Tuy Phong district, Binh Thuan province.

Through diligent research and insightful dialogues with the local populace, I've gradually deciphered the core impetuses behind these migrations, paralleling my own family's journey away from this very homeland.

This exploration is equally an earnest endeavour to decode the cultural fabric, human essence, and life experiences, which are, regrettably, fading into oblivion.

In this pursuit, I've further unearthed the enigmatic repercussions of climate change that affects a fragment of my cherished homeland.

Duy Đào (1996) is a self-taught photographer from Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. Duy is currently experimenting with photography and other mediums to narrate stories. Duy's works often revolve around the human-nature relationship, human desires, and life and death. With the desire to discover his inner self, Duy uses photography to go deeper into human life and mind. This helps him experience the world between reality and memory to find his true self.

Duy Đào

http://www.duydao.net/

Instagram: @peepsinsidehead

the solid waste dilemma

By Southida Manixay, Laos

A pressing concern takes center stage in the complex landscape of development and environmental responsibility: a significant surge in waste generation in Laos, bearing profound implications for both local communities and fragile ecosystems.

According to a World Bank study, effective waste management is primarily limited to urban areas, where only 40-60% of solid waste is systematically collected. Unfortunately, even this accumulated waste is often transported to inadequately managed landfill sites. The remaining uncollected or unrecycled garbage finds its way to open burning, burial, or dumping on open land or waterways.

Numerous regions within Laos need more essential waste management facilities and sufficient funding. While the government has initiated policies to address this issue, practical implementation remains challenging, especially in remote areas. Markets and public spaces frequently lack designated waste disposal sites, and waste separation practices are not enforced, leading many households to resort to harmful practices such as burning and indiscriminate dumping.

The repercussions of subpar waste management extend beyond national borders, affecting local communities and ecosystems. Irresponsible waste disposal in rivers disrupts delicate environments, imperiling aquatic life and exacerbating the global climate crisis. The situation worsens as waste fires release toxic heavy metals like mercury, cadmium, and lead into the soil, intensifying ecological and climate challenges. Carbon dioxide emissions from waste incineration compromise air quality and directly contribute to the climate crisis, impacting communities worldwide.

This story initially observes and documents the unadorned facts, the stark realities of waste management challenges starting in Vientiane and nearby areas. It aims to shed light on the individuals and communities grappling with these issues and their efforts to find solutions.

Southida Manixay was born in 2001 in Nakham province, Vientiane capital city of Laos. She is currently studying for her bachelor degree majoring in Product Design at the National Institute of fine arts. This was her first photography workshop.

Southida Manixay

Instagram: @bisordemon

male dove

By Saobora Narin, Cambodia

The song "លលកញីឈ្មោល" (Lerlork Nee/Chmol) translates to "Male/Female Dove'' in English. It tells the story of a male dove leaving its nest each morning to find food while the female dove cares for their young. If the male doesn't return, a hunter has likely taken his life, expressing a poignant desire for a reunion in the next life. This song hails from Cambodia's 1960s "Golden Age," marked by modernization, prosperity, and artistic flourishing, evoking nostalgia among the older generation.

Pu Han, a 46-year-old welder, reflects on a cycle where younger generations leave school to support struggling parents in low-wage jobs, perpetuating poverty. He shares his journey from quitting school to various positions, all driven by financial strain. His family's rice harvest has diminished, debts loom large, and dreams of returning to farming persist.

Long Vouchly, a climate crisis expert, notes similar struggles in rural families. Climate-induced borrowing for necessities like water pumps often leads to predatory loans and land seizures. Some families even sacrifice their meals to save money, resulting in malnutrition.

In today's era of globalization and hyper-development, Cambodia grapples with class disparities, enticing debt traps, and the looming threat of climate crisis.. The song "លលកញីឈ្មោល" echoes universal sorrow in these challenging times.

This project seeks to document the cycle of struggle, family separation due to economic and climatic factors, and the complex human stories behind the battle for survival.

SAOBORA NARIN

Instagram: @saoboranarin

NARIN Saobora is a Cambodian filmmaker, cinematographer, and photographer. Born in Kampong Thom province after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, grew up during the civil war in the 1980s.

Saobora is a Sundance Institute Fellow with over a decade’s experience in the film industry in Cambodia. He has worked on various documentaries and feature films with Academy Award-winning director Rithy Panh and was a cinematographer on Lida Chan’s feature documentary ‘Red Clothes’, which has won several festival awards. Working on a Visual Creator fairpicture.org and am also an Angkor Photo Workshop alumni from 2019.

As we look to the future we must ask ourselves what type of ancestors we want to be.

Join us, participate, be connected.

The NOOR Foundation is a non-profit organization fuelled by an unwavering passion to inspire action on the most pressing challenges of our era through the power of visual storytelling.

Education is the bedrock of our endeavours, we are called to commit to the discovery and support of emerging visual storytelling talent from a plurality of backgrounds all across the world. We facilitate the development and production of the stories that matter, learning and co-creating every step of the way. We actively promote the creation and dissemination of impactful narratives, crafting a diversified web that strives to ignite a transformative shift in how we portray and understand our world.

Our mission is to create thought-provoking, multidisciplinary visual projects that make a meaningful impact on the world and inspire purpose-driven action. We aim to cultivate an environment where a vibrant tapestry of varied viewpoints can flourish, paving the way for a truly interconnected community with narrative threads spun all over the globe.